Istanbul is -or at least was, until quite recently- not the obvious place that would come to ones' mind, when thinking about contemporary architecture.

The common conception of Istanbul is all about that unique match: A dazzling topography with an outstanding holy-imperial architecture. A city with its embedded seas and a built skyline framing it, designed as a gesamtkunstwerk of a past world power.This mainstream view however, also limits our horizon of understanding: the conception of istanbulite urbanity is overwhelmed by a phantasma of the the16th century, the age of the masterarchitect Sinan.

The metropolis beyond that "touristy bubble" is usually regarded not worth spending a glance on: It appears as "a city without architectural input". Particularly after WW II., when it grew from a "fairly big" city to a megapolis of 13 millions it has obviously lost its architectural attraction. In those decades, the city makers in Istanbul were dedicated solving the severe problem of housing for millions of new Istanbulites in quantitative terms. Indeed the architecture was mainly regarded a cost factor then and was made redundant at large.

The second, more particular glance however, reveals a space quite noteworthy in three aspects:

First come the various formations of istanbulite vernacular, dominating seemingly endless residential areas of the largest metropolis in Europe. Ranging from 19th century brick or timber houses in rows, to the classical informal 'gecekondu' of the the industrial age; from the 'apartman' townhouse of petit developers in the age of rapid urbanisation, to the 'post-gecekondus' that facelifted informal areas dramatically; from a second "savage" wave of informal urbanisation to public mass housing in chinese dimensions in recent decades; ... an outstandingly rich variety of anonymous architecture dominates the urban appearance. Often, one layer of the vernacular replaced another one, as the city was almost totally erased and rebuilt like a palimpsest, several times since early 19th century. Arkistan, does not undervalue or simply oversee the anonymous mass.

Secondly, the realm of "history" of architecture itself is by no means limited to the classics of the romano-byzantine-ottoman imperial heritage - which, without doubt constitutes a basic and standard episode of the global architectural history, not to be missed at all, and we know how to transmit that.- However, there is also a whole history of modernization between 18.-20. centuries, which is totally missed out in that classical narrative. (and became slightly part of the common consciousness through the European Capital of Culture in 2010) Modernisation is best to read through its particular history of architecture and planned/unplanned urban transformations, as architecture and planning have been used as the major tool to modernize society. But also: Actors in society reacted to the process of modernization through their own understanding of it: The bottom up architectural adaptations of whatever is understood as modern is the other,very important facette.

Periods, where actors in architectural production were strongly internationalized -like the "long" 19th century-, alternated with periods, where actors were mainly local -like most parts of the "isolated" 20th century. However, academic and intellectual trends in as well as applications of architecture as such strictly followed international trends and examples. A vivid local history of modernization was written, erased and re-written in succesive waves.

Thirdly, the recent wave of globalization that has reached Istanbul in mid/late 80s is likely to overwhelm and overwrite urban space like no period before. Till 2000s efforts concentrated -symbolic enough - in erasing the former, industrial geography at the center. Simultaneously a new iconic cityscape emerged in the newly created CBD north of the historical and republican centers. The appearance of a new skyline signifies the emergence of a new class of actors: The "big biz", increasingly merging corporate actors of finance, development and construction step in the role of city fathers. Among other things, this means clearly: architecture again, is not only affordable but necessary !

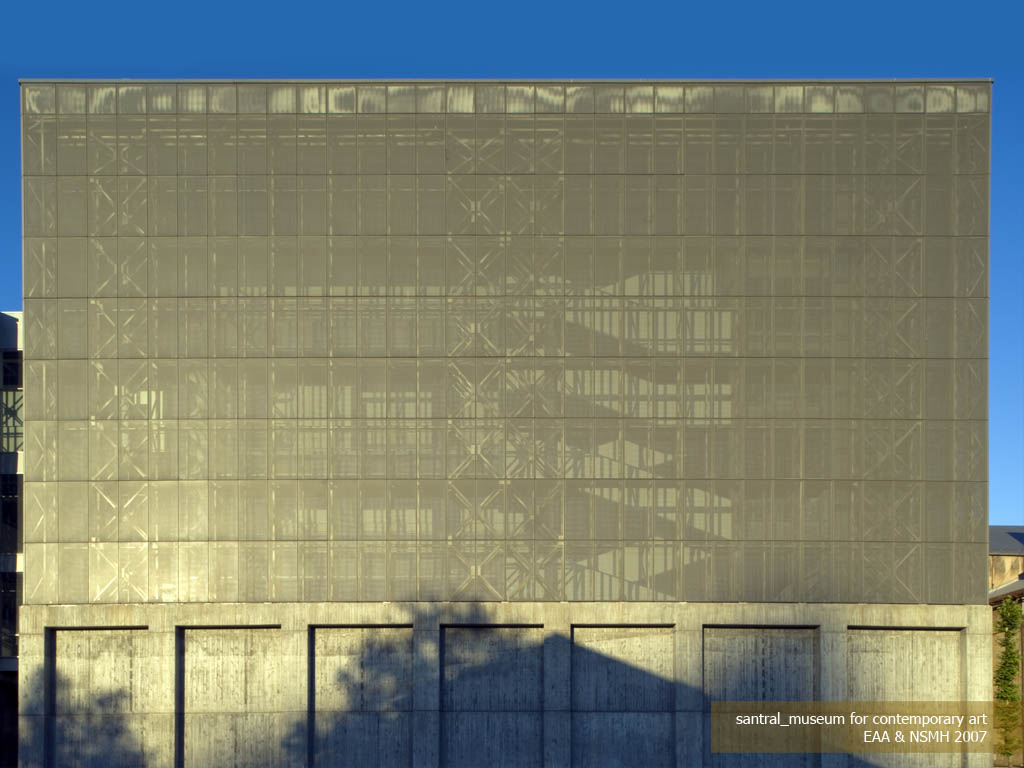

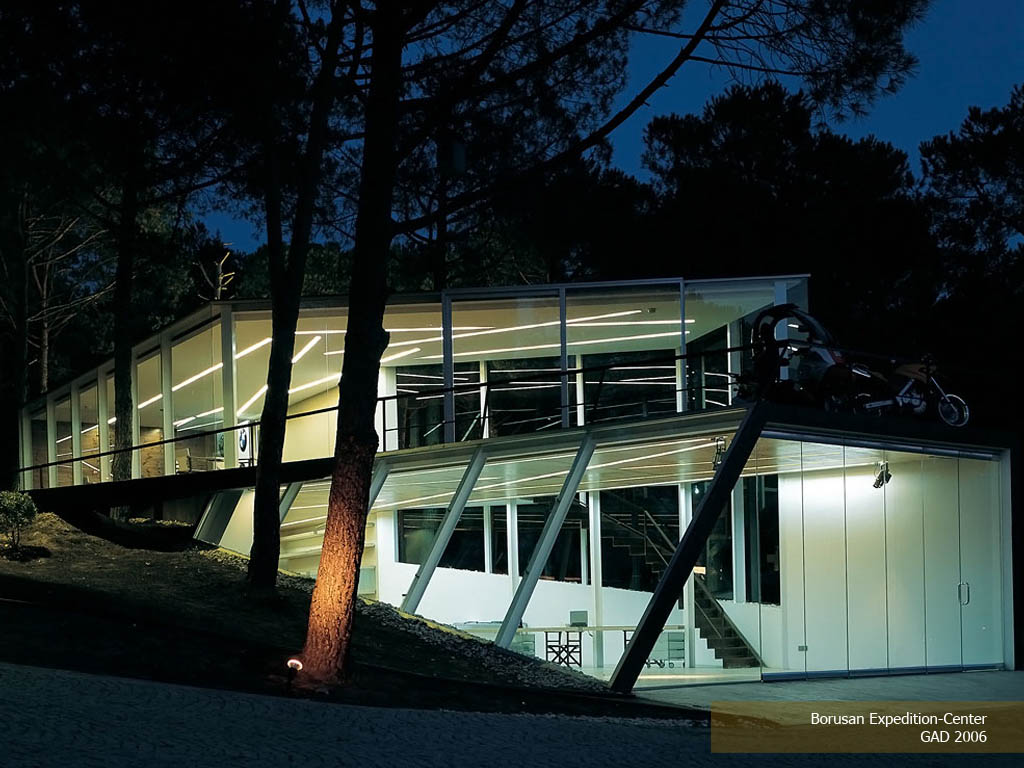

Since the last national crisis was overcome in 2003, development and construction businesses became the engine of an ever-growing economy, and a genuine production of space, mainly following the network of highways took off. Architecture in formal sense was re-inaugurated into urban space with private developments such as offices, factories, shopping centers, commercial compounds, private schools and hospitals, as well as upscale -and often gated- residential areas as typical examples. The process got irreversible when housing supply for mid and low income groups became -first time in the cities' history- a matter of larger enterprises. Marketing these, has not only put architecture increasingly on public agenda, but also helped architecture in Istanbul go beyond borders. Resources made available for architectural input have helped both local architectural production to emerge in global architectural scene (almost all important international architectural awards in last years include some nomination of an istanbulite office) as well attract architects and offices from abroad to projects around Bosphorus.

Sad enough, the culture of the public sector to obtain architectural projects has deteriorated simultaneously: while still in 70s good results in architectural design were obtained through well processed competitions, just in the age of globalization, the public has placed the process behind closed doors, which obviously did not help increase quality.